Optimizing battery electrode morphology

Designed a gradient-free topology optimization algorithm based on deep neural networks, and applied it to battery electrode.

This project challenges the current uniform electrode and hopes to develop a tool to find the optimal electrode morphology without any prior assumption on its pattern. Similar problems have been studied in topology optimization which is commonly used in solid mechanics. However, most of them are linear problems where the gradients can be easily derived. For batteries, by constrast, no gradient can be analytical obtained. As a result, current optimization algorithms cannot be used, and we designed a topology optimization algoritm called Self-directed Online Learning Optimization (SOLO). The algoritm was much faster than state-of-the-art gradient-free optimizers, and could be used to optimize electrode geometry.

Background

Since the invention of lithium-ion batteries, porous electrodes have been manufactured in essentially the same way: granulating active materials into powder, mixing them with some additives such as carbon black and binder, and pasting them on conductive substrate. Optimizations have been focusing on tuning parameters such as particle sizes, porosity and electrode thickness, with the assumption of a uniform electrode. Some recent work demonstrated better cell performance by engineering the shape of the electrode with features such as nano cylinders, tunnels and fractal branches. 3D printing has been used to fabricate the structure of batter electrode. On the simulation side, however, there have been few reports on freeform electrode shape optimization. Most shape optimizations assume a particular electrode pattern with a few adjustable dimensional parameters. Therefore, we want to propose a method to optimize porosity distribution of electrode without a prior assumption of the pattern.

Results

We first introduce topology optimization by a fluid-structure optimization example, and then look into the electrode optimization.

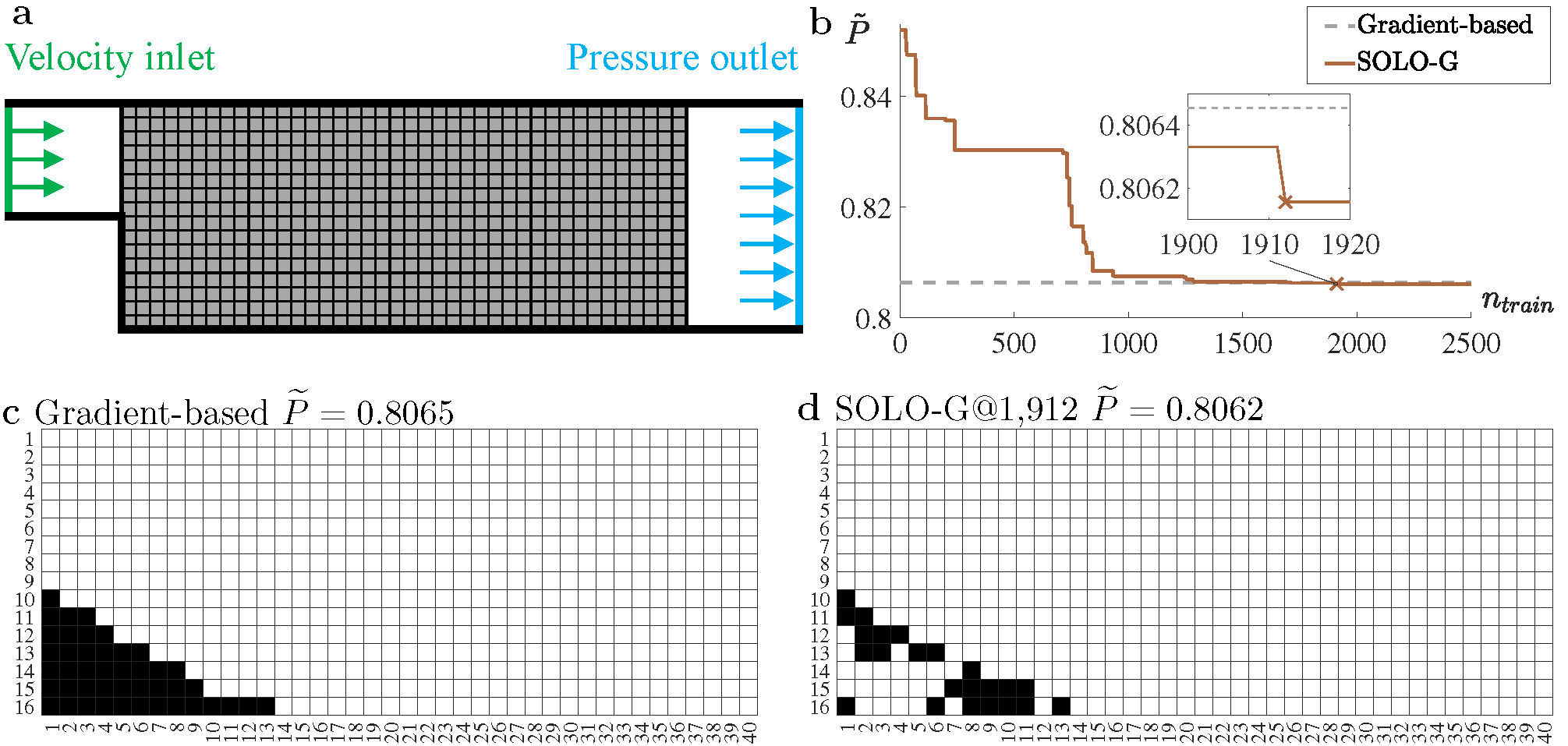

A fluid-structure example

We use an example to explain what topology optimization is. As shown in subfigure a below, the fluid enters the left inlet at a given velocity perpendicular to the inlet, and flows through the channel bounded by walls to the outlet where the pressure is set as zero. In the \(40\times 16\) mesh, we add solid blocks to change the flow field to minimize the friction loss when the fluid flows through the channel. Namely, we want to minimize the normalized inlet pressure

\[\min\limits_{\rho\in\{0,1\}^N } \widetilde{P}(\rho)={P(\rho)}/{P(\rho_O)},\]where \(\rho\) is a 640-dimentional vector with each component equal to 0 (void) or 1 (solid), \(P\) denotes the average inlet pressure, and \(\rho_O=(0,0,...,0)\) indicates no solid in the domain.

Traditionally, this problem will be converted to a continuous problem to solve by a gradient-based solver, since the dimension (i.e., number of variables) is too high for a gradient-free method. Think about all possible cases, it will be \(2^{640}\approx10^{192}\); even if each case needs one second to compute the pressure, it would take \(\sim10^{185}\) years! You cannot get the results before the end of the universe.

Our algoritm, Self-directed Online Learning Optimiation (SOLO) can significantly boost the gradient-free optimization. Subfigure b shows our pressure curve versus the gradient based (horizontal line). The algoritm only tried 1912 cases to converge (the cross “X”). Our solution (subfigure d) is better than the gradient-based method (subfigure c), since it has a lower pressure.

We just showed a binary example. In fact, we can apply SOLO to continuous problems as well. In our experiments, our algoritm outperforms many state-of-the-art gradient-free algoritms, such as CMA-ES (Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy), BO (Bayesian Optimization), and SA (simulated annealing).

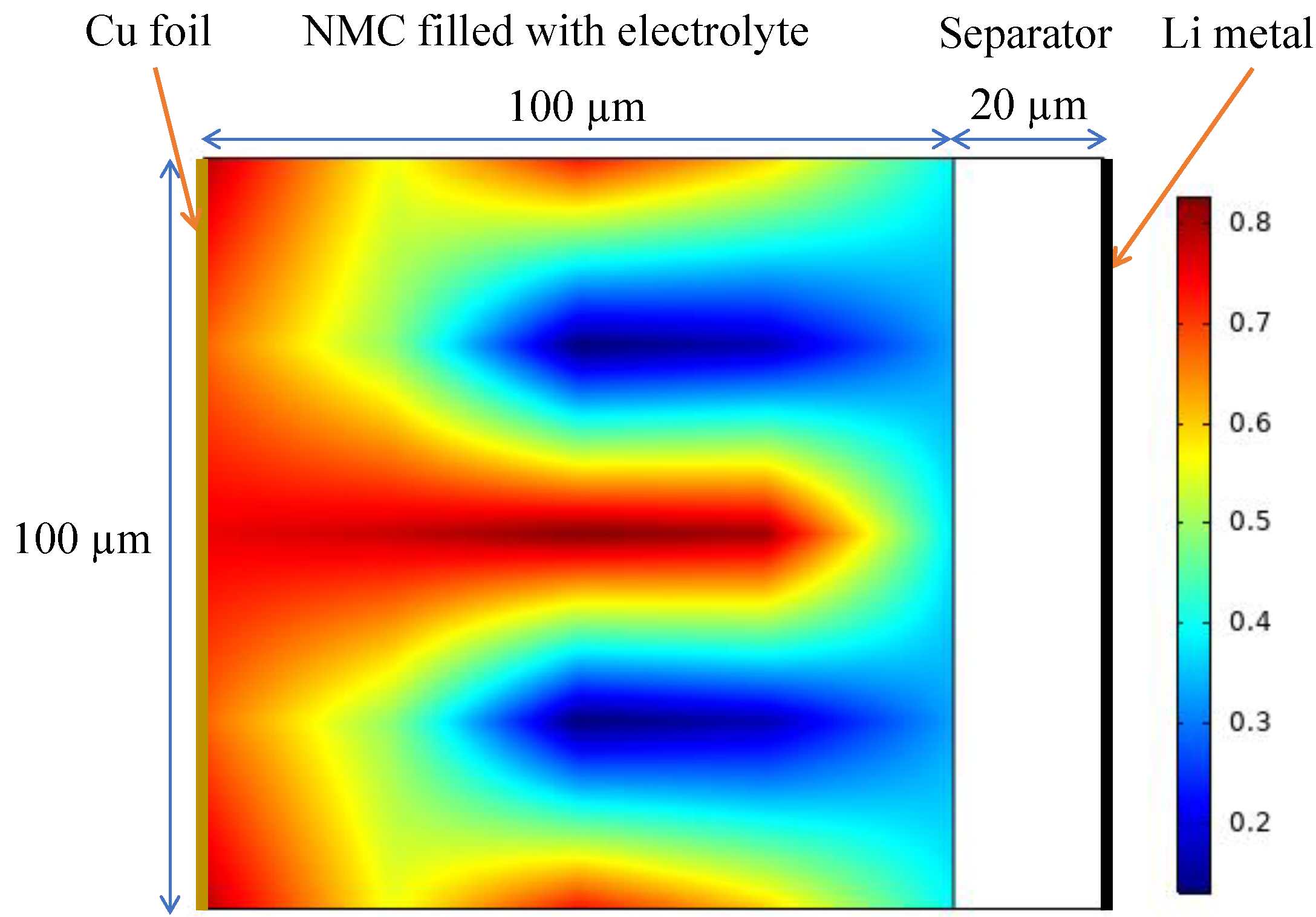

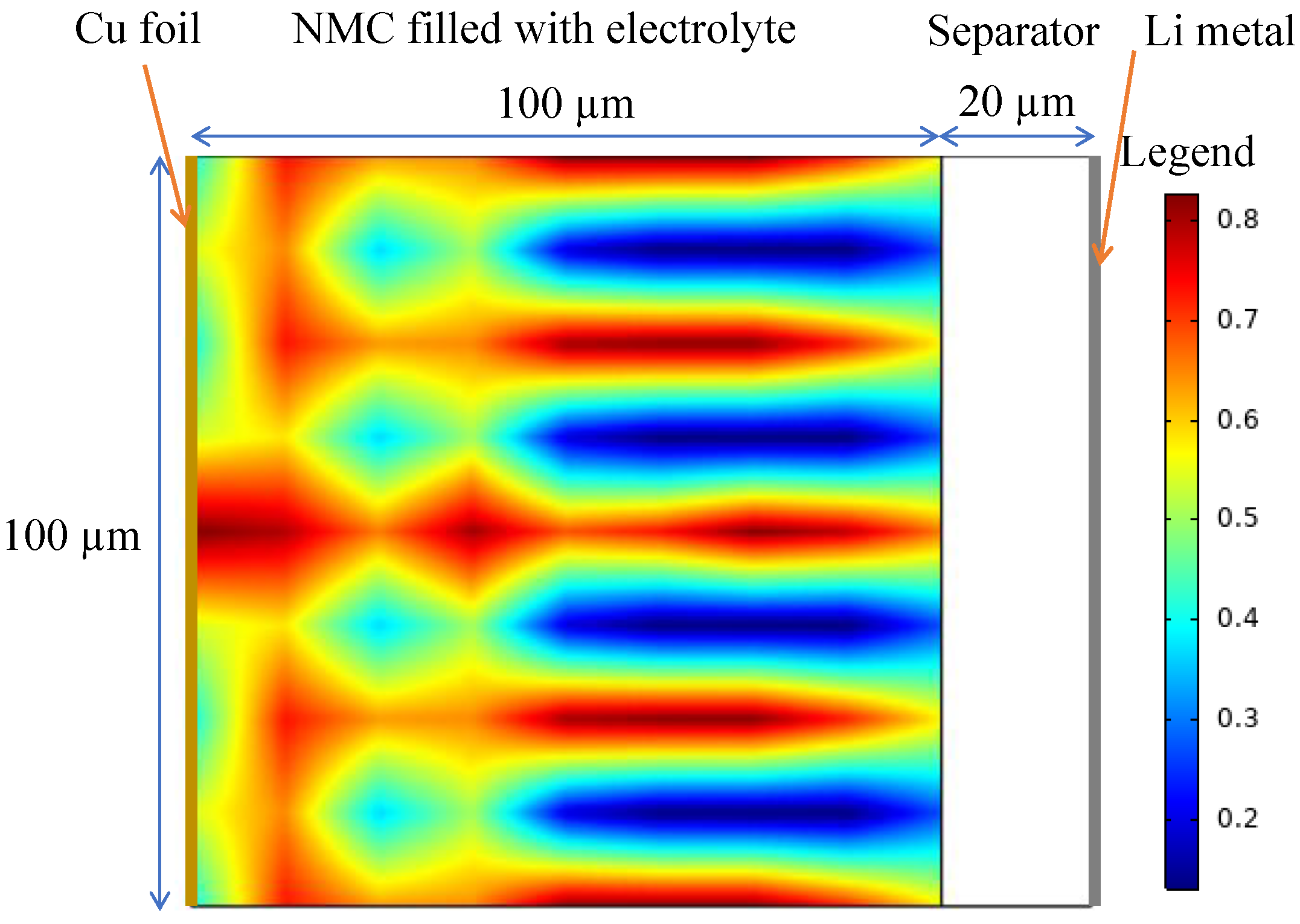

Electrode optimization

We apply SOLO to electrode optimization. Consider a NMC622/Li metal cell, We want to control the solid distribution in a domain to maximize the specific energy density:

\[\begin{array}{c} \underset{\rho=(\rho _1,\rho _2,...,\rho _N)}{\max}E(\rho)\\ \left\{ \begin{array}{l} \sum_{i=1}^N{w_i\rho _i}=0.5\\ \rho _i\in \left[ 0,1 \right] ,\text{ }i=1,...,N\\ \end{array} \right.\\ \end{array}.\]where \(w_i\) denotes the weight of integration to confine the average volume fraction of solid material to be 0.5. The specific energy \(E\) given a solid distribution \(\rho\) is obtained by discharging the cell from 4.1 V to 3.5 V, calculated by the pseudo three-dimensional model (an extension of pseudo two-dimensional model). The results are shown below.